Interest in Jungian clinical technique is growing among psychotherapy practitioners across all modalities. While Jungian theory has long attracted clinicians drawn to its creative engagement with images and unconscious material—rooted in the teleological orientation of analytical psychology—there is now increasing recognition that Jungian practice offers something more fundamental: an approach that is less hierarchical, less didactic, and deeply relational. For clinicians unable to undertake an entirely new training, Jungian supervision offers an accessible route into this tradition, providing both personal development and transferable skills for their own supervisory work. Several excellent books now address this field, and this week we feature two Jungian supervision courses offered by IAAP member societies based in the United Kingdom—programmes notably open to practitioners from non-Jungian backgrounds. What is it about Jungian supervision that makes it so intriguing, powerful, and unique?

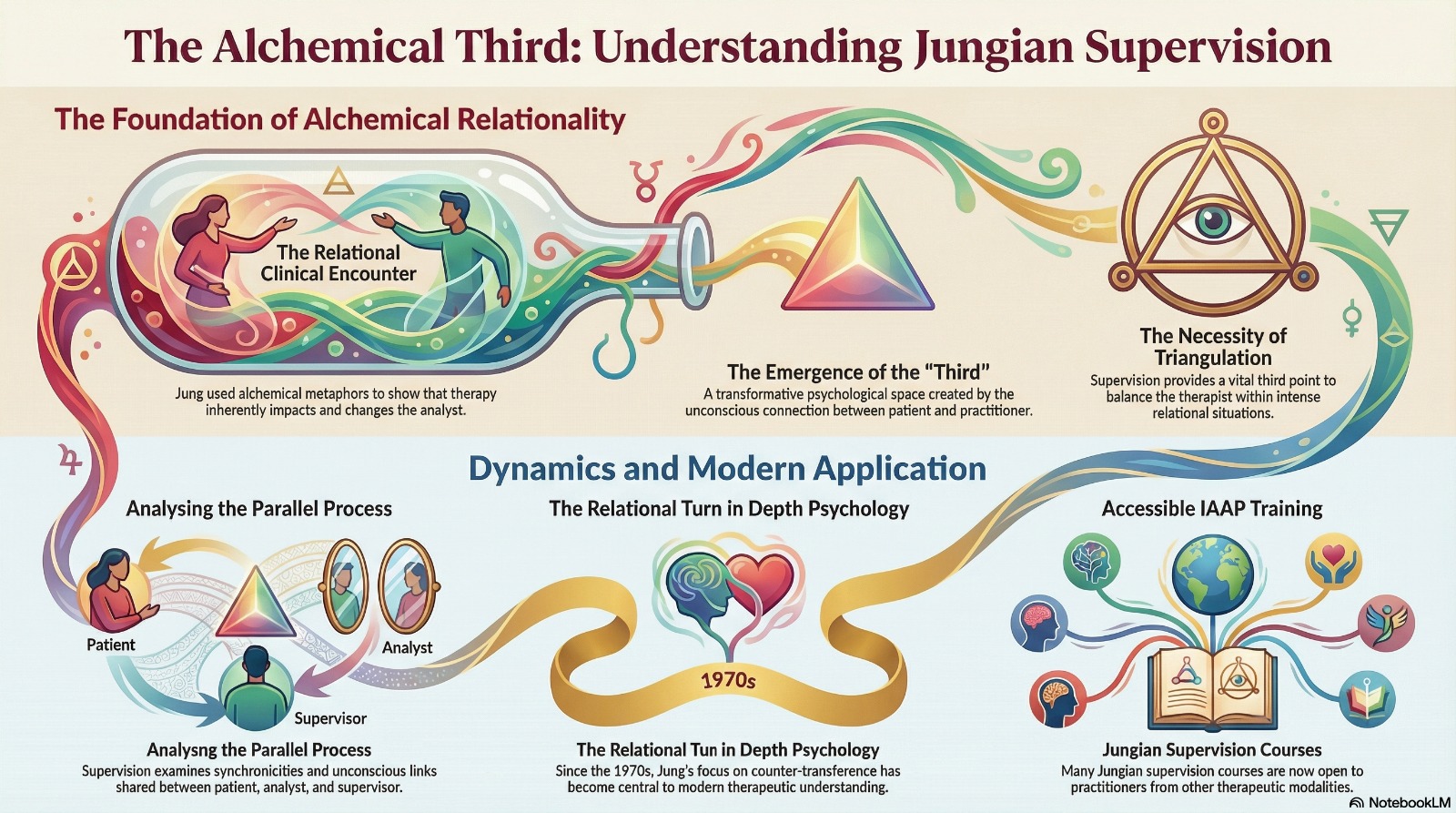

From the very beginning of his divergence from Freud, Carl Jung championed a clinical perspective that was fundamentally relational. In his seminal work The Psychology of the Transference, Jung utilized the woodcuts of the alchemical Rosarium Philosophorum to map the complex intermingling of conscious and unconscious factors between analyst and patient (Heuer, 2009). Unlike the “blank screen” model prevalent in early psychoanalysis, Jung visualized the therapeutic relationship as a “dialectical process” akin to the mixing of two chemical substances: “if there is any combination at all, both are transformed” (Jung, 1946/1966, para. 358, as cited in Bierschenk, 2009). This mutual transformation is structurally mapped in his “Gate” diagram, which depicts the cross-currents of transference and countertransference not as hindrances, but as essential components of the treatment (Heuer, 2009). By acknowledging that the doctor is as much a part of the psychic process as the patient, Jung established early on that the analyst is not an objective observer but a participant whose own personality is inevitably altered by the interaction (Bierschenk, 2009).

Because of this intense alchemical relationality, Jung recognized that the analyst required protection from “psychic infection” and the potential loss of professional perspective (Stokes, 2009). He argued that every therapist ought to have a “control” by a third person to remain open to other viewpoints and to balance the powerful forces generated within the analytic dyad (Moore, 1986). This insight led to what is essentially the first recorded request for supervision in 1909, when Jung sought Freud’s counsel regarding his countertransference difficulties with Sabina Spielrein (Martin, 2002; Stokes, 2009). Jung viewed this external support as crucial for maintaining the “hygiene” of the dyadic relationship, proposing that supervision provides a necessary “third” position or triangular space (Solomon, 2007). This triangulation allows the therapist to step out of the massa confusa of the clinical immersion and regain an analytic attitude, ensuring that the mutual transformation remains therapeutic rather than overwhelming (Stokes, 2009).

Jungian supervision is further distinguished by its unique engagement with parallel process and synchronicity, viewing these not merely as behavioral repetitions but as manifestations of deep unconscious connectivity. The concept of parallel process—where the dynamics of the patient-therapist dyad are unconsciously reenacted between the supervisor and supervisee—is understood through the Jungian lens of the unus mundus (one world), suggesting a field of resonance that transcends immediate time and space (Heuer, 2009). This perspective allows for the examination of “spooky action at a distance,” where a supervisor’s emotional experience becomes a vital organ of information about the patient’s psyche, or where a patient seemingly reacts to a supervision session they did not attend (Heuer, 2009). By treating these synchronistic events and parallel processes as significant data rather than interference, Jungian supervision illuminates the subtle, invisible threads connecting the supervisor, analyst, and patient in a shared alchemical vessel, transforming unconscious enactments into conscious insight (Stokes, 2009).

While mainstream psychoanalysis began a significant “relational turn” in the 1970s, acknowledging the analytic third and the utility of countertransference, Jungian supervision had been rooted in these concepts for decades prior (Heuer, 2009). Jung’s early insistence on the mutual influence of the analytic pair and his validation of countertransference as a “highly important organ of information” positioned Jungian supervision as historically prescient (Jung, 1929, para. 163, as cited in Wiener, 2007). Whereas early classical supervision often viewed the therapist’s emotional response as a hindrance to be analyzed away, the Jungian tradition, further developed by Michael Fordham and others, has long regarded syntonic countertransference as a vital instrument for understanding the patient’s inner world (Moore, 1986). This foundational acceptance of the intersubjective nature of therapy meant that Jungian supervision was effectively practicing a “two-person psychology” long before it became the standard in the wider psychoanalytic community (Heuer, 2009).

Today, practitioners from various therapeutic modalities are increasingly seeking Jungian supervision training because of its depth, its sophisticated handling of countertransference, and its capacity to hold the tension of the “unknown” within the clinical encounter (Mathers, 2009). The recognition that supervision requires specific competencies distinct from clinical practice has led to the development of specialized training programs that emphasize the creation of a symbolic container for the work (Hall, 2009). Responding to this demand, societies within the International Association for Analytical Psychology (IAAP), such as the Association of Jungian Analysts (AJA), now offer supervision training courses that are open to qualified clinicians from non-Jungian backgrounds (Mathers, 2009). These courses provide a unique opportunity for professionals to integrate Jungian perspectives on the alchemical third and relational dynamics into their supervisory practice, regardless of their primary theoretical orientation (Hall, 2009).

Supervision books:

On Supervision: Psychoanalytic and Jungian Analytic Perspectives

Vision and Supervision : Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives

Courses: