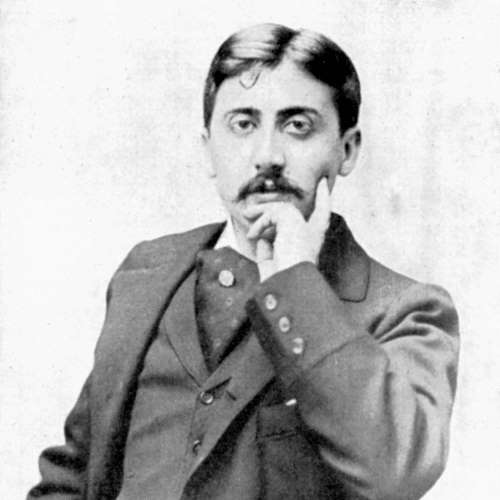

Dipping a petite, fluted, scalloped French cake, a madeleine, into a cup of lime-flower tea became the iconic vehicle or symbol of a “Proustian moment”: a sudden, rhapsodic union of childhood memories flowing into his adulthood present, creating a transcendent, unexpected pleasure of an “all-powerful joy”—a deeply felt, unwilled, chance encounter. Proust’s narrator is at first overwhelmed by this “involuntary memory” of numinous images and sensations, but he ultimately discovers that those originally unconscious memories possess a “power of expansion… which allow(s) them to resume their place in [his] consciousness” (Swann’s Way, vol. 1, p. 63). Just as in Jung’s Red Book, In Search of Lost Time chronicles the creation of an expanded self through the interplay of self-transformation and creative work.

Proust’s novel and Jung’s concepts arise in the same period. This is no coincidence. Both Jung and Proust embody the “spirit of the times” at the turn of the last century that led to revolutions in painting, literature, architecture, psychology, music, science, and philosophy. For Proust and for Jung, the self is an evolving self-creation.